|

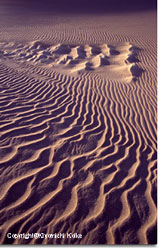

�@�O���C�g�E�T���h�E�f���[���Y

- �卻�u�����������ی�n�� - ���X�J�A�R�����h USA

�����j

�l�Ƃ̊W �l�Ƃ̊W

���ꎩ�g�S�̂̓��ƂȂ�l�͂��Ȃ��G�l�͂��ꂼ��嗤�̈�Ђł���B���̎�̂̈ꕔ .... �N���̎������������Ă����B����͎����l�ނɊ܂܂�Ă��邩��G�����Ă���䂦�ɒN�̂��߂Ƀx�����H������̂��m�낤�Ƃ��܂��G����͓��̂��߂ɖ�̂�����B

�W�����E�_��

�l�ƍ��u�F

�i�E�ʐ^�FMosca Pass Toll Stateion: Courtesy of Great Sand Dunes

National Park & Preserve�j

�i�v�I�ȂȂ���l�͂��̑��݂�m���Ă������A�K�₵�A�����đ卻�u�̋߂��ɒ����ԏZ��ł��܂����B�m���Ă���ŌÂ̐l�ނ̑��݂�11,000�N�قǑO�ɂȂ�܂��B

�������ێ�����F11,000�N�O�̌��n�l��

�T������C�X��o���[�Ƒ卻�u�n��ɑ��ݓ��ꂽ�ŏ��̐l�X�͗V�q����ł����B�t�߂ɐ������W�܂��Ă����}�����X��L�j�ȑO�̃o�C�\���̌Q����͂ނ悤�ɏW�܂��Ă����ƍl�����܂��B�ނ�͐Ί펞��l�ŁA���݃N���r�X

Clovis �ƃt�H���T�� Folsom ��[�ƌĂ�Ă���A�傫�ȐΓ����܂��͓��������g���Ď�����Ă��܂����B�قƂ�Ǒ��̒N���Ɠ����悤��400�N�قǑO�ɂȂ�܂ł́A�l�̓T���E���C�X�E�o���[�ɕ����ē����Ă��܂����B���A���̎悪�悩�������ɂ����Ŏ����߂����A����H�Ɠ�̎��͂��̒n�������Ă����̂͊m���Ȃ悤�ł��B

�����̂Ȃ���F ����A�����J�C���f�B�A��

�����̐l�X���ǂ̂悤�Ȗ��O�̌�����g���Ă��̂��͕���܂��A����̃A�����J�C���f�B�A���̎푰�̓X�y�C���l����400�N�O�ɂ��̒n�Ɏn�߂đ��ݓ��ꂽ���ɂ��̒n�Ɋ���e����ł��܂����B�`���I�ȃ��[�g����ő卻�u��

sowapophe-uvehe �ƌ����܂��B�u�O�Ɍ�ɓ����y�n�v�Ƃ����Ӗ��ł��B�q�J���[�A���A�p�b�`�͖k���j���[���L�V�R�ɒ�Z���卻�u��

ei-anyedi �u����͏㉺�ɓ����v�ƌĂт܂����B�卻�u�̂�������ނ���u�����J��s�[�N (Blanca Peak

�W����4,303�b�j�̓i�o�z�������Ȃ�R�Ǝ]����S�̎R�̈�ł��B�����̐l�X�̉ߋ��ƌ��݂̂Ȃ���Ƃ͉��Ȃ̂ł��傤�H

�q�J���[�A���A�p�b�`�Ɠ샆�[�g���ɂƂ��āA����͌����I�Ȗ��ł��B�ނ�̓T���E���C�X�E�o���[�Ŗ�h����������̂ł��B�ނ炪���u�ɂ������A�H�p�����Ė�p�Ƃ��Ďg���Ă����|���f���[�T�p�C��

Ponderosa pine �̖X��������̕\��w���W�߂Ă��܂����B���I�E�O�����f�ɉ������n��ɏZ��ł����e��/�e�B��

Tewa/Tiwa ���b���v�G�u�������炫���l�X�ɂƂ��ẮA����Ƃ̃����N�������̂ł����B�ނ�͂��̍��u�ߗׂ̃T���E���C�X�E�o���[�Ɉʒu����A�ނ炪�����Ɍ����鎞�ɒʂ蔲���Ă��̂���Ƃ�����A�傫�ȏd�v�������`���I�Ȉ�Ղ��L�����Ă��܂��B

�u�����̓��[�g�����ȑO�悭�W�܂��Ă����ꏊ�̂ЂƂł����B...

�L���v���^ Capulta ��c�͂��̒n��ŃL�����v���������A���ł����B�ߏ��̉Ƒ������͂����ɗ��Ĕނ�ƈꏏ�ɃL�����v�����̂����H���Ԃ�t�̏��߂��H���[�܂������������ł��傤�B���[�g���͈��ړI�A�����ĐH�����Ƃ��āA�|���f���T�p�C������\����g���Ă��܂����B....

�����̕�������Ĉ��������Ă����̂ł��傤�B��������Ď��n���Ă��܂����B����N��ɂȂ�܂ł́A�Ⴂ�q�ǂ���������`���܂������A��{�I�Ɏ�����̎��n�͏������̎d���Ŕޏ��������X��I��ł��܂����B....

�v

�A���f���E�i�����S Alden Narango�A�샆�[�g�����j��

�X�y�C���l�ɂ��T���F

Don Diego de Vargas, 1694

Juan Bautista de Anza, 1776

���݂̖k���j���[���L�V�R�B�ɂ������X�y�C���A���n����q�v���l�����炭�������1598�N���ɂ͂��̒n�ɓ����Ă����ł��傤���A1694�N�Ƀh���E�f�B�G�S�E�f�E�o���K�X

Don Diego de Vargas ���T���E���C�X�E�o���[�ɓ��������ƂŒm����ŏ��̃��[���b�p�l�ƂȂ�܂����B�f�E�o���K�X�Ɣނ̕��������͂ǂ����o���[�암�ŁA�T���^�E�t�F�ɖ߂�O�ɁA�o�C�\�����݂��Q���500����������悤�ł��B

1776�N�ɂ́A�R�}���`���̈�R�ɕU������������̋A�蓹�ɁA���A���E�o�E�e�B�X�^�E�f�E�A���U�ƂƂĂ��Ȃ������̑��߂������ƒ{���āA���炭���̍��u�̋߂���ʂ����悤�ł��B���̍��̃T���E���C�X�E�o���[�́A�R�}���`���A���[�g���A�����ăX�y�C���������ɂƂ��āA�����n�тƃT���^�t�F�̊Ԃ̗��s���[�g�ł����B�ł�����A�ނ�̑����ɂƂ��ăg���[�����猩���鍻�u��������ׂɂȂ��Ă������Ƃł��傤�B 1776�N�ɂ́A�R�}���`���̈�R�ɕU������������̋A�蓹�ɁA���A���E�o�E�e�B�X�^�E�f�E�A���U�ƂƂĂ��Ȃ������̑��߂������ƒ{���āA���炭���̍��u�̋߂���ʂ����悤�ł��B���̍��̃T���E���C�X�E�o���[�́A�R�}���`���A���[�g���A�����ăX�y�C���������ɂƂ��āA�����n�тƃT���^�t�F�̊Ԃ̗��s���[�g�ł����B�ł�����A�ނ�̑����ɂƂ��ăg���[�����猩���鍻�u��������ׂɂȂ��Ă������Ƃł��傤�B

���ւ̊g���F

Zebulon Pike, 1807

�[�u�����E�p�C�N��1807�N�̎�L�ɏ�����Ă��鍻�u�Ɋւ���L�q�͋��炭�m���Ă���ŏ��̏��ʂł��傤�B���C�X�E�A���h�E�N���[�N�T�����͓��ɖ߂��čs�������ɁA�p�C�N�č����R���т͉����̓A�[�����T�[��b�h����o�[�Ɏ���قǂ̉����܂ł̒T���𖽂����Ă��܂����B1806�N11�����܂łɃp�C�N�Ɣނ̕��������͍����̃R�����h�B�v�G�u����������Ƃ���܂ő���i�߂Ă��܂��B����ɓ쐼�Ɍ������A�������Ȃ���A�[�J���T�[��̈ʒu��c���ł����������Ȃ���A�p�C�N�͒��x�卻�u�̏�̂�����̃T���O����f��N���X�g�R�����z���Ă��܂����B�ނ�1807�N1��28���̎�L�ɂ��ƁF

�u���}�C���s�i��������ɁA��X�͔�������....�����R�X�̘[�Ɂi�����̃T���O���E�f�E�N���X�g�R���j�����������čs���ƁA���̋u��������....�L�����v���͂荻�u�Q�̒��̍ł��������̂ɓo���Ă݂��B����Ɩ]�����������đ傫�Ȑ�i���I�E�O�����f�j�����邱�Ƃ��ł����B....���̋u�͏�艺�肵�Ĕ����R���Q�̘[�ɉ�������Ă���̂��������B����͂P�T�}�C�����炢�����ĕ��͂T�}�C�����炢�Ɍ������B�����͐F�����Ⴆ�A�����̏�ɂ͐A���̈�l�����Ȃ��A���x�C�ōr��闒�̒��̔g�̂悤�Ɍ������B�v

John C. Fremont, 1848

John Gunnison, 1853

1848�N��

1n 1848, John C. Freemont

was hired to find a railroad route from St. Louis to California.

He crossed the Sangre de Cristos in the San Luis Valley in

winter, courting disaster but proving that a winter crossing

of this range was possible. He was followed in 1853 by Captain

John Gunnison of the U.S. Topographical Survey. Gunnison's

party crossed the dunefield on horseback: "Touring the

southern base of the sand-hills, over the lowest of which

we rode for a short distance, our horses half burying their

hoofs only on the windward slopes, but sinking to their knees

on the opposite, we for some distance followed the bed of

the stream from the pass, now sunk in the sand, and then struck

off across the sandy plain�cThe sand was so heavy that we were

six hours and a half making ten miles�c"

Routes into the Valley

In the years that followed,

the Rockies were gradually explored, treaties were signed

and broken with resident tribes, and people with widely differing

goals flooded into Colorado from the United States and Mexico.

In 1852, Fort Massachusetts was built and then relocated to

Fort Garland, about 20 miles southeast of the Great Sand Dunes,

to safeguard travel or settlers following the explorers into

the San Luis Valley.

Although many settlers arrived

in the San Luis Valley via the trails from Santa Fe or La

Veta Pass, several routes over the Sangre de Cristo Mountains

into the San Luis Valley were well-known to American Indians

and increasingly used by settlers in the 1800s. Medano Pass,

also known as Sand Hill pass, and Mosca Pass, also called

Robidoux's Pass, offered more direct routes form the growing

front-range cities and dropped into the San Luis Valley just

east of the Great Sand Dunes. Trails were improved into wagon

routes and eventually into rough roads. The Mosca Pass Toll

Road was developed in the 1870s, and stages and the mail route

used it regularly through about 1911. That year, the western

portion was badly damaged in a flash flood. Partially rebuilt

at times in the 1930s through the 1950s, it has been repeatedly

closed by flooding and is now a trail for hikers.

Making a Home: Homesteaders

Homesteader Ulysses Herard,

who with his family established a ranch and homestead along

Medano Creek in 1875, would have used the old Medano Pass

Road to travel to and from his home. The modern road, open

only to 4WD, high clearance vehicles, follows the old route,

skirting the dunefield before rising to Medano Pass and continuing

east into the Wet Mountain Valley. The Herards grazed and

bred livestock in the mountain meadows, built a home, raised

horses, cattle, and chickens, and established a trout hatchery

in the stream.

Other families homesteaded

near the Dunes as well, including the Teofilo Trujillo family,

who raised sheep west of the Dunes. And Frank and Virginia

Wellington, who built the cabin and hand-dug the irrigation

ditch that parallels Wellington Ditch Trail, just south of

today's campground. Their son, Charles, ran a sawmill on Sawmill

Creek, just north of the campground.

As people established homes,

they often petitioned the U.S. Postal Department for post

offices to serve their tiny villages. Zapata (1879); Blanca

or North Arrastre; Orean (1881); Mosco (1880); later called

Montville (1887-1900); Herard (1905); Liberty (1900); Duncan

(1892) and others helped connect isolated homesteaders with

the larger world.

Seeking Wealth: The Gold Rush, 1853 and later

Gold and silver rushes occurred

around the Rockies after 1853, bringing miners by the thousands

into the state and stimulating mining businesses that operate

to this day. Numerous small strikes occurred in the mountains

around the San Luis Valley. People had frequently speculated

that gold might be present in the Great Sand Dunes, and in

the 1920s, local newspapers ran articles estimating its worth

at anywhere from 17 cents/ton to $3/ton. Active placer mining

operations sprang up along Medano Creek, and in 1932 the Volcanic

Mining Company established a gold mill designed to recover

gold from the sand. Although minute quantities of gold were

recovered, the technique was too labor-intensive, the stream

was too seasonal, and the payout was too small to support

any business for long.

Preserving the Beauty: Establishing a National Park Service

Site

The idea that the Dunes could

be destroyed by gold mining or concrete-making alarmed residents

of Alamosa and Monte Vista. By the 1920s, the Dunes had become

a source of pride for local people and a potential source

of tourist dollars for local businesses.

Members of the Ladies PEO

sponsored a bill to Congress asking for national monument

status for the Great Sand Dunes. Widely supported by local

businesses and Chanbers of Commerce, the bill was signed into

law in 1932 by President Herbert Hoover.

Living at the Dunes

Imagine: you are standing on the edge of a shallow lake, surrounded

by cattails and birdsong. The dunes hover on the horizon to

the north. You're carrying a small fiber pouch filled with

sharp flakes of stone, and you're wearing very little-to what

time do you belong? Or again, it's a summer day and you're

bridling your horse at Montville, Colorado and listening to

the flies buzz. You wear the blue and gold of a cavalryman.

When and where are you? And once again: you're digging a shallow

pit in the side of an old grass-covered dune. Carefully you

photograph the layers of different colored sandy soils you

observe before digging deeper. What are you doing-and why?

Students in the future may

be able to identify all three of the characters sketched above

as people who lived part of their lives at the Great Sand

Dunes, thanks to a four-year research project that began summer

2000. "This is a pretty neat project," states Resource

Specialist Fred Bunch. "It's really a chance to look

at all kinds of different reasons that all kinds of different

people visited the dunes over a long, long time." Bunch

is coordinating this project, but it's an interdisciplinary

group of researchers and volunteers who are making it happen,

including scientists who specialize in archeology, anthropology,

geology, ethnography, and the Great Sand Dunes staff.

Traditionally, Great Sand

Dunes National Park has been known as a 'geology' park - one

where the most obvious stories revolve around the landscape

and its formation. Questions about the dunes and how they

formed continue to be some of the most commonly asked. However,

local history tells the human side of the story as well; there

is plenty of oral and written evidence of people visiting,

passing by, or living for a time near the dunes. The Great

Sand Dunes Eolian System Archaeological and Ethnographic Project

is an attempt to better understand how people have interacted

with the land around the dunes over time.

Some of the basic questions

this project addresses and the researchers involved include:

How have people through time used

what appears, at first glance, to be a constantly changing

landscape? Dr. Richard Madole is a geomorphologist, one who

studies the formation and evolution of landforms. He is concentrating

on the 'eolian system'-that is, the wind influenced sand deposits-with

a focus on understanding how the dunes, sand sheet, and sabkha

have changed over time, and when those changes occurred. With

that data, he and his colleagues can then consider how those

changes could have affected people in the area.

How has climate change affected how

people lived near the dunes over the past 13,000 years? Drs.

Pegi Jodry and Dennis Stanford, a wife and husband team of

archaeologists from the Smithsonian Institution, have been

working in the San Luis Valley for years. In summer 2000 and

2001, they surveyed or excavated several sites near springs

on the Medano Ranch, just west of the main dunefield. "The

Medano Ranch is really a wonderful opportunity," says

Dr. Jodry. "We can gather data about human use there

from Clovis times [about 12,000 years ago] to the present.

It's amazing to think about, but the larger story of ancient

humans in the San Luis Valley is really about how they adapted

to the changing availability of water. As wetlands expanded

or contracted over time, people used different options for

making a living." For more on Pegi's and Dennis' work

in the San Luis Valley and beyond, see the December 2000 issue

of the National Geographic Magazine and Volume 2 (1) of American

Archaeology Magazine.

How were pin-juniper forests of foothills

used through time? Pin-juniper forests offer plentiful resources

to hunters and gatherers-pin nuts, fuel, habitat for game

animals-and so can give glimpses of how people in the past

made their living near the dunes. Archaeologists Ted Hoefer

and Marilyn Martorano and their teams began surveying known

sites in the pin-juniper forest of the foothills east of

the dunefield in summer 2000, after a wildfire had burned

over many of the sites. In summer 2001, they continued their

work and included Denton Springs and Montville, both sites

that were occupied or used by ancient people as well as more

modern ranchers, settlers, park visitors, and park staff.

What do American Indians living today

have to say about the dunes and the San Luis Valley? Ethnographer

David White began contacting tribes with ties to the San Luis

Valley in 2000, initially focusing on the Jicarilla Apache,

the Tewa Pueblo, and the Ute as groups known to have traditionally

used or visited the area. In the next phase of his research,

he hopes to contact the Tiwa and Towa Pueblos, the Navajo,

the Comanche, Cheyenne, and Arapaho. For some of the people,

the connection is not so much one of subsistence as spirituality-the

Jicarilla Apache still collect sand from the dunes to create

sand paintings used in healing ceremonies, and the Tewa regard

the San Luis Lakes, just south of the dunes, as an important

part of their creation story. Dr. White is quick to point

out that the ethnographic story of the area is much larger

than the current project, and could easily include the descendants

of other tribes as well as of the European, Hispanic, and

Asian people who settled in the San Luis Valley in the last

few centuries.

Want to learn more about who was here, when, and why?

Pick up a copy of "The

Hourglass" at the Visitor Center, for a summary of some

of the findings from the archeology project described above.

Ask at the Visitor Center to see the video "Sacred Trees"

which features members of the Ute tribe describing how ponderosa

pine trees in the monument were used by their ancestors.

Consider purchasing "A Colorado Pre-History: A Cultural

Context for the Rio Grande Basin", authored by several

of the researchers mentioned here. Available at the Visitor

Center bookstore, and may be found in your local library.

�@

�@

[���̃E�F�u�T�C�g�́A�A�����J�̎��R�̕�̈�ł���卻�u�̔����������Đ_����Љ�邽�߂ɍ���܂����B���T�C�g�̑S�Ă̓��e�͓����������T�[�r�X�ɃT�|�[�g����Ă��܂��B�T�C�g�͓��p�����ō���Ă��܂��B�g���Ă���S�Ă̎ʐ^�͏��r���ʎB�e�A���쌠������܂��̂Ŗ��f�̎g�p�͂��T�����������B�ŏ��̔����ʐ^�͓����������̂��D�ӂɂ���Ďg�p�����Ē����Ă���܂��B]

|